'A revolutionary time': How law and science are working together to secure the rights of nature

Climate change and biodiversity loss are intimately linked, and there are useful lessons for those involved in both topics to learn from each other. This month we look at how science can support legal cases on the rights of nature

Mika Peck was studying the brown-headed spider monkey, a critically endangered primate, in a cloud forest in northern Ecuador in 2005 when he was contacted by a group of local people waging a long-running war against an open-pit copper mine.

The group wanted to gather data about the kinds of animals and plants that lived in the Intag Valley’s unique ecosystem to build a case to shut down the site and Peck agreed to help.

Peck says the transnational companies that initially bought up the mining concessions had a concerning approach to environmental and human rights. But it was not until the site was taken over by the state mining company in 2014 that it came under the clear jurisdiction of Ecuador and a legal challenge became a realistic proposition.

In March, an Ecuadorian court revoked the environmental license granted to Ecuador’s Empresa Nacional Minera and Chilean copper producer Codelco for Llurimagua, a US$3bn copper-molybdenum project in the Intag Valley, because it violated the rights of nature enshrined in the country’s constitution since 2008 and breached the rights of local people who had not been properly consulted about the project. Mining activity has now been suspended.

“This victory was possible thanks to the decades-long struggle of the people of Intag who faced intimidation because of their work,” Mario Moncayo, a lawyer who worked on the case, told ELaw.

They were helped by specialised ecological evidence provided by a team in which Peck, now professor of conservation ecology at the Uni of Sussex, was involved. The team also provided evidence for a similar landmark case in nearby Los Cedros in 2021.

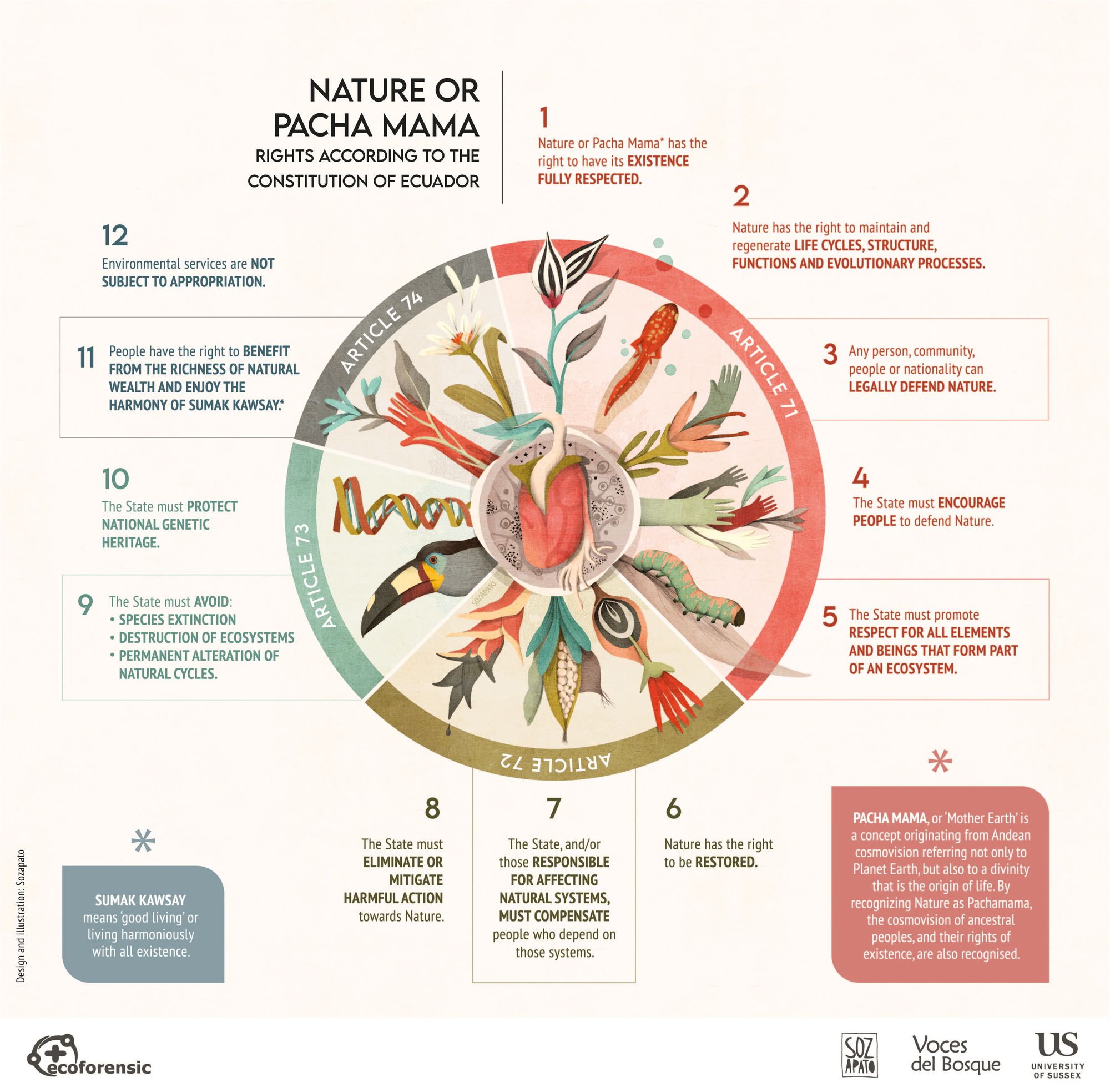

Under Ecuador’s rights of nature laws, the state must avoid species extinction, and it’s fairly easy to show this, says Peck (see chart below).

The rights of nature in the Ecuadorian constitution. Illustration by Sozapato, kindly adapted from an original artwork by Sozapato commissioned by Ecoforensic in association with Voces del Bosques

Researchers were looking for critically endangered, endemic species, ideally with important functional roles in the local ecosystem. Drawing on the IUCN Red List, they managed to get a list of 15 threatened species for the Intag Valley court case; a risk assessment by the mining company’s own consultancy only uncovered a handful.

“What we needed was to highlight how important that area was,” says Peck.

The evidence base for the cases relied on years of work from both national and international scientists; Ecuadorian researchers made the astonishing find of the rare longnose harlequin frog, which played a major role in winning the Intag Valley case.

Meanwhile, the animal that Peck had studied for decades was “very, very important” in the court case for Los Cedros. “We proved that, without the spider monkey in the forest system, seeds of hardwood trees (which is what the loggers want) won’t be propagated, because it’s the only thing that disperses the big seeds. That’s the ecological function role that was deemed very important and the mine put that at risk.”

Challenges for ecologists

It is much harder to gather evidence that animal or plant life-cycles are being disrupted or evolutionary processes are being harmed - all of which are also protected under Ecuadorian law. “Those are challenges for ecologists,” says Peck. “Our job really now is to work out how the hell do we generate these sorts of datasets within a legal framework?”

While people have been bringing lawsuits on environmental issues for thousands of years, the current crop of biodiversity cases is different.

Like climate litigation, and in some cases inspired by its success, it is more strategic in nature. As an expert told me for an article in the Guardian last year, a better understanding of ecosystem dynamics, the increasingly central role of science in lawsuits and greater judicial awareness of the systemic nature of the problem are helping lawyers choose and structure their cases more carefully.

The International Rights of Nature Tribunal, a peoples' court set up by the Global alliance for the Rights of Nature (GARN), has gathered a wide range evidence from scientists, lawyers, Indigenous people and others to give its verdict (albeit completely non-legally binding) on a variety of cases. It recently declared Mexico guilty of violating the rights of nature and the rights of Mayan peoples due to the construction of the 'Tren Maya' railway.

Peck recognises that many scientists are already working on this topic, but says more robust studies and dedicated resources are needed to build a strong evidence base to protect ecosystems under rights of nature legislation. He is developing a specialist field that draws on both ecology and law that he term ‘ecoforensics’ and set up a non-profit organisation with the same name to provide long-term support for communities.

Another effort to give the rights of nature more scientific rigour is the interdisciplinary More Than Human Rights (MOTH) project. This delves into the work of botanists, ecologists, mycologists and animal behaviour experts who are blurring the boundaries between the human and the non-human, for example by exploring what counts as intelligence, sentience and the ability to solve problems.

The project was set up by César Rodríguez-Garavito, professor of clinical law as well as chair and faculty director of the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice at NYU School of Law. He hopes it will help lawyers and human rights practitioners build arguments and legal cases just as attribution science has built a rigorous scientific base for climate litigation.

Could sperm whales being tortured be represented in court one day? (Photo: Bernard Spragg)

Attempts to directly uphold such rights for animals have so far been unsuccessful in the West; last year a US court ruled that Happy the elephant could not be legally considered a person. But Rodríguez-Garavito imagines a near future where people represent torturted sperm whales using evidence generated by an AI project which is close to decoding their language.

MOTH is even exploring how to defend old-growth forests on the basis of the rich underground mycelium resources that they harbour - an idea that throws up complex jurisdictional questions. “It’s about taking advances in science and applying them to litigation to expand the sphere of what lawyers and judges are prepared to protect,” says Rodríguez-Garavito.

Dr Helen Dancer, senior lecturer in law and anthropology at the University of Sussex who is lending her legal skills to the Ecoforensic project, says that, just as the recognition of rights of nature has been really paradigm shifting, courts could become more innovative about the kind of evidence they consider. “I think there’s an opportunity to be creative here, but it’s important to consider what kinds of evidence courts find persuasive or credible. There’s a lot at stake.”

"There is no ‘Urgenda’ for rights of nature yet.. but I think the momentum is building"

The legal field is playing catch-up with the hard sciences, agrees Rodríguez-Garavito.

Climate change was unknown when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was made 75 years ago and is now widely acknowledged to be a threat to human rights. However, says Rodríguez-Garavito, even the most progressive parts of legal academia are still fundamentally anthropocentric. “We’re still in the phase where people are sceptical or at least on the fence about the rights of nature. It disrupts the basic language of rights.

“But that separation between humans and nature, and nature and culture, is no longer tenable, both because the scientific underpinnings are being questioned and because the consequences of that paradigm are out there for everyone to see: climate change, pollution, biodiversity loss.”

Rodríguez-Garavito considers the Ecuadorian court’s rulings the most sophisticated in the world in upholding the rights to nature, but notes that they are still unusual. “There is no ‘Urgenda’ for rights of nature yet.. but I think the momentum is building.”

He adds that climate litigation practitioners should be looking beyond their silos to see how rights of nature can bolster their own arguments and facilitate the inter-cultural translation of legal arguments with Indigenous peoples.

Transition period

In June, Peck and Dancer travelled to Ecuador to meet with the judge who ruled on Los Cedros and other legal experts, with the aim of better supporting rights of nature cases in future.

They have also been training the local community to collect ecological evidence so they can continue protecting the ecosystem and raise the alarm for species extinction. These paraecologistas get a crash course in scientific methods and then monitor their area alongside professional scientists. Some have gone on to become scientists themselves.

Peck says Ecuador’s constitution is still in a “transition” period following its recognition of the rights of nature, and is working out how these rights play out against other rights to private property and underground resources. “What interests me as an activist ecologist is how you can put this thing into practice.”

Ecoforensic is also working in three other communities in Ecuador and is expanding its work to Brazil, where it is helping communities in Minas Gerias state affected by mining establish rights of nature legislation. And it has been invited to go to the Ivory Coast to look at how the new EU law on deforestation-free products could be monitored locally.

“I think it’s a revolutionary time,” says Peck.