Why language matters to climate justice

How can language can be a barrier to accessing and upholding the law, and how can it be overcome?

Hamtramck is a small city in Michigan surrounded almost entirely by the much larger metropolis of Detroit. It is densely populated and its mostly low-income community includes a large proportion of immigrants and people of colour.

In early 2020, the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) approved a significant change to the licence of a hazardous waste plant in the city, allowing its operator US Ecology North to increase storage capacity nine-fold.

Frustrated about the decision to expand the site in Hamtramck, which already houses another commercial hazardous waste facility just to the south as well as a number of other industrial sites, the community rallied and filed a discrimination grievance.

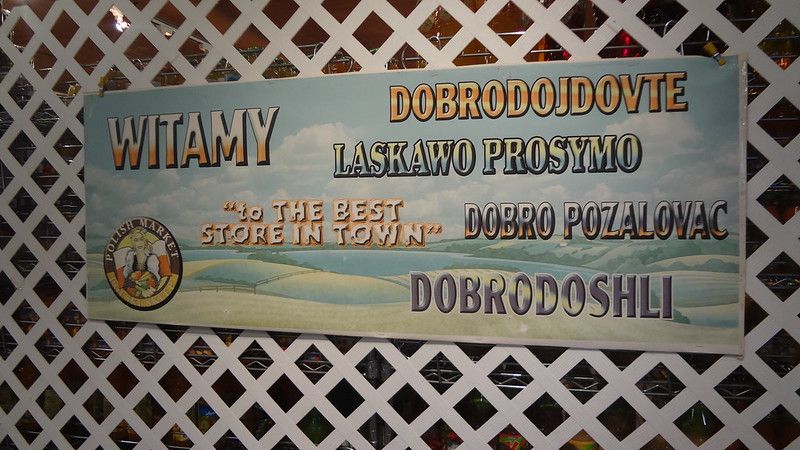

The complaint said EGLE failed to provide translations of public notices and documents relating to the licence application into languages other than English, or appropriate interpretation, and argued that this stopped a significant proportion of the Hamtramck population – many of whom speak English as a second language – from properly getting involved in the consultation process.

This, they claimed, violates Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which prohibits discrimination against people on the basis of national origin by recipients of federal funds. In particular, they referred to an important 1974 Supreme Court ruling known as Lau v Nichols.

Overall, the complainants said the environment department showed a “pattern of neglect and disregard” in licensing commercial hazardous waste facilities “that has resulted in these facilities being disproportionately located in communities of color”.

Across the US, more than half of those who live close to hazardous waste are people of colour but the problem is particularly egregious in Michigan. A 2007 study on environmental justice by the United Church of Christ found that the percentage of people of colour living near commercial hazardous waste facilities was 66% in the state, compared to 19% in areas without such facilities - the most disproportionate situation in the whole of the US.

According to the claimants, that pattern continues today.

That matters because it exacerbates health inequalities; there is a wealth of evidence that people of colour in the US breathe more toxic air and are more likely to die from pollution.

While the Hamtramck case is not explicitly about climate change, industrial facilities like the one being challenged are often big emitters in and of themselves and are exacerbating the effects of climate change on vulnerable communities.

For Andrew Bashi, staff attorney at the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center, which is supporting the grievance, language is “super important” and can be a barrier even for those with English as their mother tongue.

“Even for us as environmental attorneys, it can be very, very complicated,” he says, “and then to expect lay people, more often than not communities that are predominantly minority Black and brown, immigrant communities that traditionally have much lower rates of high school graduation, of literacy, to be able to understand these super complex laws and come up with a comment that the state is going to take into consideration is almost impossible.”

Bashi was one of the co-authors of a recent paper in the journal Environmental Justice, which notes that infrastructure, land use, zoning and permitting decisions have long perpetuated patterns of environmental racism in the US.

I ask Bashi whether he thinks the language of environmental law, replete with its own complex terminology, is intended to exclude people. He says he “goes back and forth” on this issue, “but the impression from folks on the ground is that this is definitely the case, that things were drafted and created in a way that makes it inaccessible.

“And I think they have every right to think that way. To me it does make it, at the very least, purposely kind of exclusionary in terms of public participation because it limits what comments are really considered in making those decisions.”

He adds that the law is often used as a shield because it is so technical. “So it's very easy for an administration to say or an agency to say, ‘Well, what we're doing can't be discriminatory because we're following the text of the law’. I think that's bullshit. Because by using racially neutral language they basically have found a way to continue discriminatory treatment. And when you use that type of language, it basically puts the onus on everybody else to do their research and understand the context within which you're making a decision.”

The Hamtramck claimants are currently in an informal resolution process with the state, which would not comment any further as negotiations are ongoing.

Communication problems

Language barriers to accessing justice are not just a US problem.

Research in the UK by the Bell Foundation found gaps in language support were a big problem for access to criminal justice and rehabilitation. As well as people actually in prison or on probation, it affected victims, witnesses, defendants and detainees with the result that important information was not being passed on and fundamental rights were being denied.

And nor is it only an issue within a country; it is a cross-border problem too.

Juana Alonzo Santizo left her native Guatemala in 2014, hoping like many for a better life elsewhere. But instead she was imprisoned along the way in Mexico where she remains to this day.

When she was arrested, Santizo could only speak Chuj, an Indigenous language. According to the UN Office for Human Rights in Mexico, she was interrogated without legal representation or an interpreter to help her understand the charges or proceedings - all which were in Spanish - and she felt pressured into signing a self-incriminatory statement.

This prompted environmental scientist Dr Jessica Hernandez, climate justice strategist for the Mayan League, to tweet earlier this year in a Twitter account takeover that this was essentially a case of climate injustice:

Yesterday was International Mother Language Day. I wanted to highlight how being denied access to our Indigenous languages can result in injustices that are rarely amplified. As the climate justice strategist for @MayanLeague I wanted to draw your attention to a case...

— Gage—Discover Brilliance (@Gage_500WS) February 22, 2022

While it is unclear exactly what prompted Santizo to leave Guatemala, it is certainly considered one of the countries most at risk of extreme weather worsened by climate change and also one of the most vulnerable.

Dr Hernandez has written and spoken extensively about how colonial frameworks continue to shape academia and the importance of recognising and centering Indigenous knowledge about the environment. She says this applies to language too, where Indigenous concepts of how the Earth should be cared for are embedded in language and are difficult to translate. For example, in many Indigenous languages there isn’t even a word that translates to conservation.

This is echoed in a recent paper published in Lancet Planetary Health, which argues that the disregard for linguistic issues in public health policy-making is rooted in colonial practices and exacerbates risks to people's health and quality of life.

“Really, until we change the law to affirmatively acknowledge that people of colour have been discriminated against for all this time and… find a way to repair those wounds that we've created, we're just going to keep doing the same thing,” says Bashi.

Quick fix?

However, compared to deeper issues of structural racism, he argues the language problems can be “easily changed”.

The study in Environmental Justice, led by Natalie Sampson, associate professor of public health at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, finds that plain language can make environmental decision-making processes more transparent and meaningful.

To address environmental justice, it concludes, “agencies must reflect on how and why they are soliciting public participation in environmental decision making”.

“Of course, there are capacity challenges for doing this work well, but as with all [environmental justice]-related efforts, administrations and agency directors can choose to prioritize their commitment to addressing environmental racism. Systems must be designed to enthusiastically encourage and support public participation, not deter it, and anything less will continue to perpetuate systems of inequity.”